In August 2016, I travelled to Gurdaspur in northern Punjab, close to the border with Pakistan, to photograph a judo training centre for The Wall Street Journal. It was my first trip to the state. The coach, Amarjit Shastri, a former Sanskrit teacher and trade union leader, had been training kids, mostly from impoverished Dalit families, in a barebones facility behind the local government school. For many families, the centre’s training regimen was a ploy to keep their kids away from drugs, and for a few, it was the prospect of a government job under a sports quota.

This year, something unexpected happened. One of Shastri’s students, 24-year-old Avtar Singh, became the first Indian judoka to qualify for the Olympics in over a decade. Singh was on his way to Rio, so we followed two brothers, Rohit, 15, and Sajan, 14, who showed promise in the sport.

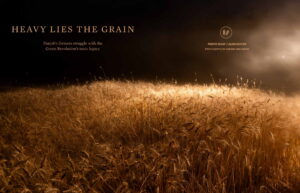

Postscript: At some point during the two days we spent working on the story, Shastri and I started chatting about Punjab and the drug menace. He told me about Punjab’s agrarian crisis and how it was partly responsible for young men from the state falling prey to drugs. I was intrigued and wanted to know more. I returned to Punjab two months later to better understand the origins of the crisis in Punjab’s farmlands and kept going for the next eight years, resulting in Heavy Lies the Grain.