Jarnail Singh, 43, lights lamps beside the tubewell on his paddy farm, a day after Bandi Chhor Diwas, which falls on the same day as Diwali, in Nihal Singh Wala in Moga, Punjab, India. November 13, 2023.

Singh claimed to be one of the last farmers standing in the rapidly expanding town limits and was certain that he would be the last one to continue harvesting, despite the many challenges.

Heavy Lies the Grain

India extracts more groundwater than any other country, surpassing even the combined usage of the U.S. and China. The primary driver of this demand is agriculture, especially in the northwestern states of Punjab and Haryana.

The origins of this thirst can be traced back to the Green Revolution of the 1960s. Battling persistent food shortages and dependence on grain imports, Indian planners hoped to attain self-sufficiency in food production. They provided farmers with high-yielding seed varieties, chemical fertilisers, and pesticides and also helped mechanise farming tools and equipment.

In Punjab, a focus area, farmers were encouraged to shift from traditional crops such as pulses, maize, and oilseeds to rice and wheat. As a result, the area under wheat cultivation more than doubled between 1960 and 2023, with production rising more than ninefold. Rice cultivation saw even steeper increases, with land use increasing nearly 14-fold and an astonishing 58 times more production of the grain. Today, Punjab, which represents 1.53% of India’s geographical area, produces about sixteen percent of the country’s wheat and eleven percent of its rice.

Rice requires a lot of water, between 3000 and 5000 litres for every kilogram of grain produced. Farmers initially relied on canals for water, but they soon began drilling tube wells, pipes bored deep underground, to tap into aquifers. The number of tube wells in Punjab increased from 200,000 in 1970 to more than 1.5 million today, said Samanpreet Kaur, a groundwater expert at the Punjab Agricultural University. Eighty-six percent of Punjab’s available water resources are now being used for agriculture, and 75 percent for rice alone.

According to a report from the Central Ground Water Board, water levels in Punjab are dropping at an average of almost 20 inches per year. The tube wells used to be located at 100 to 150 feet. “Now they have reached up to 400 to 500 feet,” said Sunil Mittal, a soil and groundwater expert at the Central University of Punjab. He explained farmers are now hitting aquifers surrounded by minerals such as uranium, lead, and arsenic, which are entering the water used for both agriculture and household consumption. These heavy metals, along with nitrates in fertiliser runoff, may have contributed to increasing rates of cancers and kidney diseases.

Photographed between 2016 and 2024, the project investigates the impact of decades of intense monocropping on Punjab’s agriculture, water resources, health and farm debt. It also examines how climate change exacerbates the crisis.

Reporting on this project between 2023 and 2024 was supported by a grant from the National Geographic Society.

Publications:

The Caravan Magazine and Undark.

Talks:

Jesus College, University of Cambridge, UK.

South Asia Forum, Queen Mary University of London, UK.

Centre for World Environmental History, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK.

Indian Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, India.

Kanak means gold in Sanskrit. In Punjabi, a language that evolved from Sanskrit, it has come to mean wheat.

Wheat lit up by the lights of a harvester in Sema in Bathinda, Punjab, India. April 27, 2024.

Labh Singh, 65, is a small farmer with 2.15 acres of land in Khiala Kalan in Mansa, Punjab, India. November 22, 2017.

During the Green Revolution, farmers in Punjab were encouraged to move away from traditional pulses, maize, and vegetables and to grow wheat and rice paddy instead.

The Bhakra Canal, photographed at Khanauri in Sangrur, Punjab, India. January 30, 2024.

The canal carries water from the Bhakra Dam, built over the Sutlej, to irrigate over 10 million acres in the states of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan.

Harwant Singh, 60, checks his phone as he waters his wheat crop, when it was his turn to draw water from the canal, at night in Gehri Devi Nagar in Bathinda, Punjab, India. January 23, 2024.

During the early years of the Green Revolution, farmers primarily relied on canals for irrigation. With the introduction of tubewells, farmers no longer had to wait for their turn to draw water from the canal, which could sometimes be at inconvenient hours. The introduction of free power for farms in 1997 contributed to the wider adaptation of tubewells and the rapid depletion of groundwater resources.

Village elders spend an evening at Satth, a platform that serves as a communal space, in Kotra Kalan in Mansa, Punjab, India. November 21, 2017.

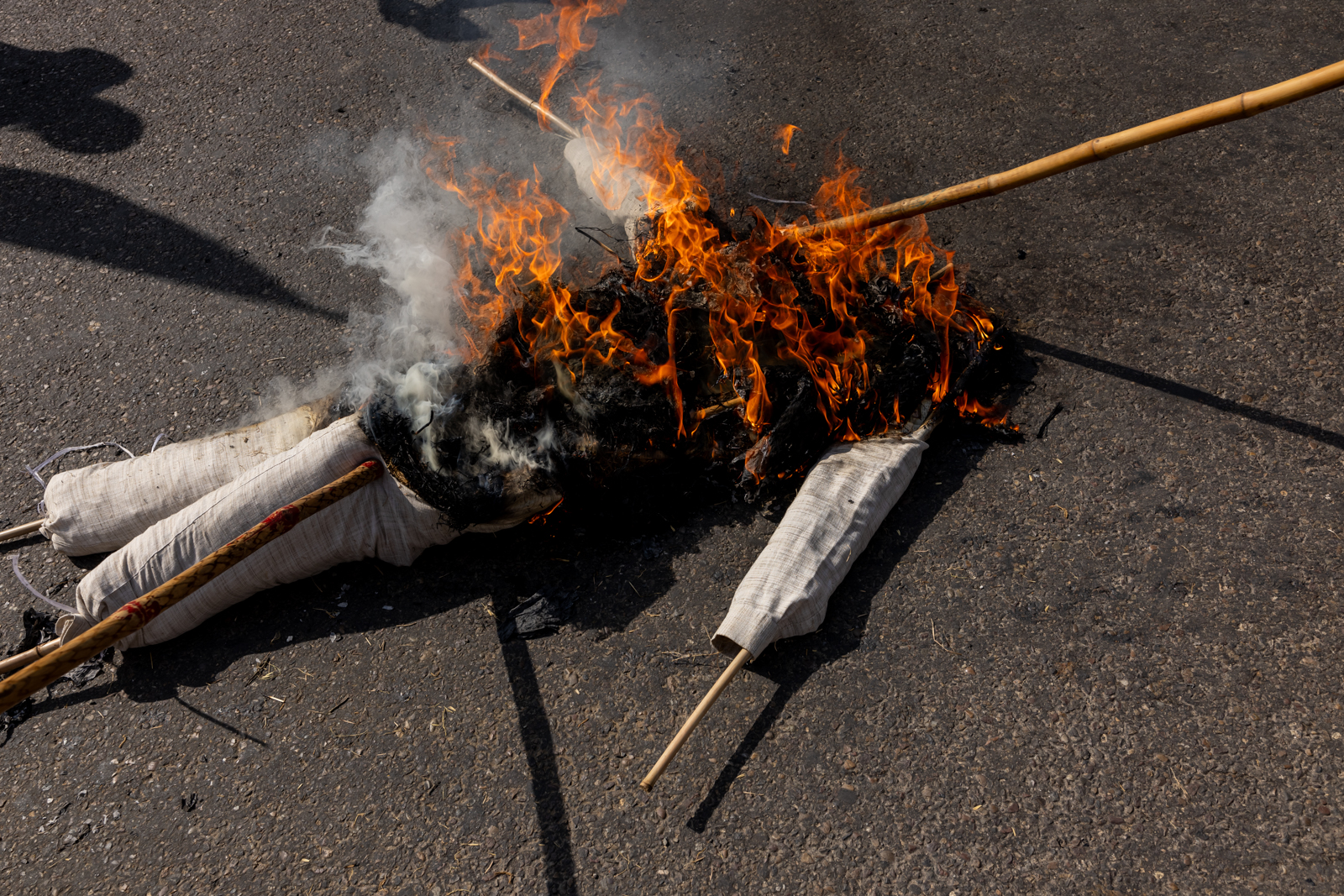

Farmers from 130 villages that have no access to canal water and are dependent on tubewells for irrigation burn an effigy during a protest in Dhuri in Sangrur, Punjab, India. October 03, 2023.

Being in the ‘dark zone’ for overexploitation of groundwater, farmers in most of these villages are not allowed to dig new tubewells, and some said they have to leave their lands fallow owing to the lack of water.

Farmworker Buta Singh, 55, washes his hands after spraying a cocktail of fungicide, insecticide, and nutrient supplements in a desperate attempt to improve paddy yield Nangal Kalan in Mansa, Punjab, India. September 29, 2023.

During the first two months of the monsoon season, Mansa received 45 percent less rainfall than average, which resulted in crop underdevelopment and lower yields.

A migrant worker from Bihar photographed as he was applying mustard oil over his skin to protect it from the early-winter cold, at a grain market in Bhagu in Bathinda, Punjab, India. November 11, 2023.

Ram Swarup, 50, a farmer, watches the receding waters of the Ghaggar in Sadhuwala in Mansa, Punjab, India. July 26, 2023.

The Ghaggar, a seasonal river, was in spate after receiving heavy inflows from the upper reaches of the Himalayas, attributed to climate change by scientists.

Gurnishan Singh, 45, poses at his home, which was destroyed by the flood waters of the Beas in Bhaini Kadar in Kapurthala, Punjab, India. More than two months after the flood, his four-acre land is still underwater, and he is still waiting for compensation. October 08, 2023.

The floods destroyed standing crops in 18,000 acres around the village, and many farmers reported no harvest during the crop season.

Nanku, 14, assists his father Gurbakshan Singh in keeping stray cattle away from the fields in Makha in Mansa, Punjab, India. January 29, 2017.

The family is employed collectively by the village’s farmers and gets paid in wheat, which they sell in the market to meet their expenses.

Paddy stubble set on fire near Sema in Bathinda, Punjab, India. November 06, 2023. Every winter, farm fires in Punjab are blamed for contributing to the dense smog over Delhi.

Representatives of a farmer union hold a press conference at a field where a Happy Seeder has been used in Dhaula in Barnala, Punjab, India. December 11, 2019.

The machine was sold as a solution that mulched paddy stubble while sowing wheat simultaneously, avoiding the need to burn stubble. However, the leaders said such fields, just like the one they were standing on, were prone to severe pest attacks.

A worker harvests cotton on a farm in Thutianwali, Mansa, Punjab, India. November 18, 2017.

The southern part of Punjab was long regarded as the Cotton Belt, but repeated white fly and pink bollworm attacks in the last few years forced many farmers to switch to paddy, which in turn added to the stress on water levels.

Chopped maize, to be used as cattle fodder throughout the year, is being unloaded in a pit outside a farmer’s home in Bhaini Bagha in Mansa, Punjab, India. July 25, 2023.

Over the past few years, many farmers have taken to sowing maize as a third crop during the summer months, resulting in greater groundwater extraction.

Baljinder Singh Mann, 27, is a weather blogger from Balloh in Bathinda, Punjab, India and has tremendous reach across Punjab and Punjabi-speaking parts of neighbouring Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, and Rajasthan. He had a reach of 2.8M in the preceding 28 days on Facebook and 4.2M views on Instagram. July 27, 2023.

Mann regularly receives messages from farmers seeking advice on when the weather would be good to sow seeds, spray pesticides, etc. He says he has seen drastic changes in the weather patterns in the five years he has been a weather blogger, with the state receiving more rain during the North-Eastern monsoon than the South-Western monsoon and parts of Punjab receiving either more or less rain than usual.

After walking door to door to collect milk for the local gurudwara, a group of young men sit in the back of a makeshift pick-up truck in Sukhpura Maur in Barnala, Punjab, India. December 10, 2019.

A farmer sleeps atop his paddy harvest at the Grain Market in Bathinda, Punjab, India. November 09, 2023.

The previous month, untimely rains across the state damaged standing paddy crops and caused harvested paddy to build up high moisture. Government regulations bar agencies from purchasing paddy with more than 17 percent moisture content, while many farmers report as much as 20 to 24 percent. They either sell it to commission agents who deduct 2 percent from the overall weight to account for excess moisture or wait to sell it at the markets, hoping the grain dries.

Avtar Singh, 30 and Paramjeet Kaur, 30, with their only son Vinaypal Singh, 8, at their home in Joga in Mansa, Punjab, India. July 28, 2023.

Singh’s family owns 10 acres, and following a trend seen across Punjab, the couple decided to have only one son so that their land wouldn’t be further fragmented.

Landless farm labourers at a National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) work site in Bhaini Bagha in Mansa, Punjab, India. October 01, 2023.

The Act guarantees registrants up to 100 days of work. Though the works are usually carried out when there is no regular work in the fields, the women here said increased mechanisation of farm work, coupled with the shift away from cotton, leaves them without work for most days of the year.

Pooja Rani, 23, and Arun Saxena, 28, during their pre-wedding shoot at Shoot Villa, a location that offers a vintage Punjabi village ambience, among other backdrops, for photo shoots in Bathinda, Punjab, India. November 07, 2023.

Workers unload sacks of milled rice at a Food Corporation of India warehouse in Mehma Bhagwana in Bathinda, Punjab, India. January 20, 2024.

The rice and wheat purchased by FCI are routed to the Public Distribution System program, which provides free and subsidised food grains to those in need across India. Though Punjab constitutes only about 1.5 percent of India’s land mass, grains from the state in recent years have made up substantial portions of this central pool. In the 2023-2024 production year, rice from Punjab was 25 percent of government procurement from farmers for the program; the state also contributed nearly 50 percent of the wheat.

Water gushes out of a freshly installed tube well in Burj Mahema in Bathinda, Punjab, India. April 29, 2024.

Vikramjeet Singh, the farmer, lost his monsoon crop of cotton to a pest attack and the winter wheat crop to an unprecedented hailstorm in early March. He hopes the tubewell will help him switch to the water-intensive but reliable paddy instead during the monsoons.

An advertisement for a medical diagnostic centre outside Bathinda, Punjab, India. November 14, 2023.

Maluck Singh, a registered medical practitioner, has been serving the local community in Lalluana, in Mansa, Punjab, India, for 23 years. October 02, 2023.

Singh, who is very well respected by the villagers, especially for his work during the COVID-19 pandemic, said that he has been observing a higher prevalence of kidney stones, high blood pressure and diabetes, as well as more cancer cases among villagers.

At Phulad in Sangrur, Punjab, India, someone added a Google Maps placemark over the Ghaggar, which flows past the village, as the “Cancer River”.

Bimla Devi, 40, is a cancer survivor from the village who believes that it is indeed the water that caused her stomach cancer two years ago. October 04, 2023.

A cancer patient from Punjab, onboard the train from Bathinda to Bikaner in neighbouring Rajasthan, which is infamously referred to as the Cancer Express. November 29, 2016.

Chest X-rays being dried at the Acharya Tulsi Memorial Cancer Research Center and Hospital in Bikaner, Rajasthan, where many from Punjab go for cheap and accessible cancer treatment. The train that carried most of these patients was locally referred to as the Cancer Express. November 30, 2016.

Women from farming families gather to make rotis as Seva, voluntary work or service, at the local Gurudwara in Gobindpura in Mansa, Punjab, India. May 08, 2024.

Govarthan Nath, 27, is a behrupiya who dresses up as characters from Indian folklore and walks around in villages in Punjab during the days following Diwali, entertaining kids and accepting gifts from the villagers. Nath, a farmer in Chikli near Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh, says he does this for fewer days now as farmer incomes have dwindled, and they are not as generous with gifts as they used to be. Gehri Butter in Bathinda, Punjab, India. November 14, 2023.

The funeral pyre of RD, an ex-farm worker who died after consuming pesticide, in Nihal Singh Wala in Moga, Punjab, India. November 13, 2023.

Karanjeet Kaur, 37, consoled her husband Ranjit Singh whenever he was worried about Rs. 700,000 (USD 11,000) debt, the result of three years of failed crops, and threatened to kill himself. She ensured that he was never alone, but one day in 2011, he went to the farm and hung himself with his turban. Kaur now works as a farm labourer, providing for her daughter (17) and a son with special needs (16) in Kot Dharmu in Mansa, Punjab, India. January 27, 2017.

A cancer screening camp organised by Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital from Sangrur in Cheema in Sangrur, Punjab, India. October 07, 2023.

Cancers are widely reported across the state, especially in the south, and many farmers believe the chemicals from the farm are causing them.

Sukhmander Singh, 60, from Bajakhana, Moga, undergoes dialysis at a state-run centre in Bathinda, Punjab, India. January 24, 2024.

Singh had quit farming six years ago, after it became tough for him to work the farm owing to his kidney disease. Singh, who owns 5 acres of land, gave it away on lease and currently has a medical debt of about INR 400,000 (USD 4820). Singh is certain the disease was caused by the huge amounts of pesticides and fertilisers used for farming. Farmers earlier used cow manure in their fields but shifted to chemical fertilisers because of the ease and effectiveness, and that has in turn led to the water and food being polluted with chemicals, he said.

Kalwinder Kaur Sidhu,45, lost her husband Kaldeep Singh to suicide four years ago, after working up a debt of Rs. 600,000 (USD 9400) on their son’s cancer treatment.

Karnveer Singh,13, didn’t survive despite the family’s best efforts. Sidhu, who now suffers from a debilitating back pain, leased out their 4-acre farm in Talwandi Akhliya in Mansa, Punjab, India. January 28, 2017.

Balwant Singh, 35, works with his brother Gurbans Singh, 48, to clear a small patch of land to grow vegetables without chemical inputs for their own consumption, in Dadde in Bathinda, Punjab, India. September 30, 2023.

“We use pesticides in such quantities that anything you eat in Punjab is bound to give you acidity, if not some serious ailment,” he said.

Protesting Punjabi farmers remove police barricades put up on one of the roads that lead to the protest site at Singhu outside Delhi, India. December 08, 2020.

In 2020, Punjabi farmers marched to Delhi on their tractors and laid siege to the city’s borders for over a year, protesting against three new farm bills that were passed by the central government. Among the bills’ several contentious clauses, farmers are most worried about the withdrawal of a minimum support price (MSP) for farm produce. They were afraid private players would offer low prices in the absence of a regulatory mechanism, pushing many of them out of farming and eventually leading to the corporate takeover of agriculture.

Farmers under a makeshift tent propped up between tractor-trailers at the Tikri protest site.

While the farmers protesting at Singhu come from the wealthier Majha and Doaba regions of Punjab, the ones at Tikri come from Malwa, which also records most of Punjab’s farmer suicides. December 14, 2020.

Protesting farmers watch a film on the occupied highway at Singhu, outside Delhi. December 09, 2020.

Farmers take selfies with Punjabi singer Kanwar Garewal at the Tikri protest site outside Delhi. The protests received a great deal of support from singers and artists from the region, and the anger against the Farm Bills is being channelled through music. Ailaan, one of Grewal’s songs that went on to become a protest anthem, was later taken down by YouTube, prompting complaints of yielding to pressure from the Indian government. December 14, 2020.

Amarjeet Singh Dhillon, 47, has moved away from the traditional rice-wheat production cycle at his farm in Bargari in Faridkot, Punjab, India. January 21, 2024.

He now grows 30-35 varieties of fruits and vegetables on his 12-acre farm, which is planned in a way that some produce is always harvested and sold locally.

He said the signs of the water crisis were always there, but haven’t been paid much attention to. “The main problem with paddy is that it is profitable. The yields, prices, and purchase are guaranteed. Why will farmers move to other crops?”

Barricades put up by Haryana’s police blocking the highway at the state’s border with Punjab at Khanauri. May 10, 2024.

On February 13, 2024, hundreds of farmers set off to lay siege to Delhi’s borders, demanding a legal guarantee for MSP on all crops. However, Haryana police stopped them at the state’s borders at Shambhu and Khanauri. They stayed put at the borders for 13 months before they were forcefully evicted on March 20, 2025.

The horse of a Nihang warrior Sikh at the farmer protest site at Punjab’s border with Haryana at Khanauri. May 09, 2024.

Kaur Singh, 60, from Lehra Mohabbat in Bathinda at the farmer protest site at Punjab’s border with Haryana at Khanauri. May 10, 2024.