Indigenous Murias spend an afternoon under a banyan tree in Balimera.

The Muria isn’t Home

In 2005, the government of Chhattisgarh in central India raised an armed civilian vigilante group called the Salwa Judum (Peace March or Purification Hunt in Gondi) to complement the security forces in combating Maoist rebels in the state. Given almost unlimited powers, the Salwa Judum soon outgrew its mandate and became a feared name in the jungles of Chhattisgarh.

Caught in the crossfire between security forces and Maoists, many indigenous Muria tribals undertook a long and hazardous passage to the neighbouring state of Telangana. Here, too, they continue to be harassed by police and forest officials.

In 2011, the Supreme Court of India disbanded the Salwa Judum, terming it illegal and unconstitutional. Several NGOs have since facilitated the Murias’ transition back to their respective villages, but most opted to stay back rather than revisit memories of home, where the conflict had no resolution in sight.

August 2013.

A maize farm abutting a house in a Muria settlement at Balimera in Telangana’s Khammam district.

Khammam district in Telangana, which shares a long border with Chhattisgarh, has 16,000 displaced Murias living in 203 settlements on either side of the Godavari river.

Vanjam Aitamma leads her cattle to graze in the forests at Lankapalli. Forests on both sides of the state border are abundant in Mahua, a tree around which the lives of Murias are centered.

A stream floods the road to Thatigonde. The settlement, like many others, is cut off during the monsoon when the streams are in full spate.

Taati Rudriah at his farm in Kondapuram.

The Muria settlement at Tellarayigudem, owing to its proximity to a revenue village, has electricity and access to a hand pump.

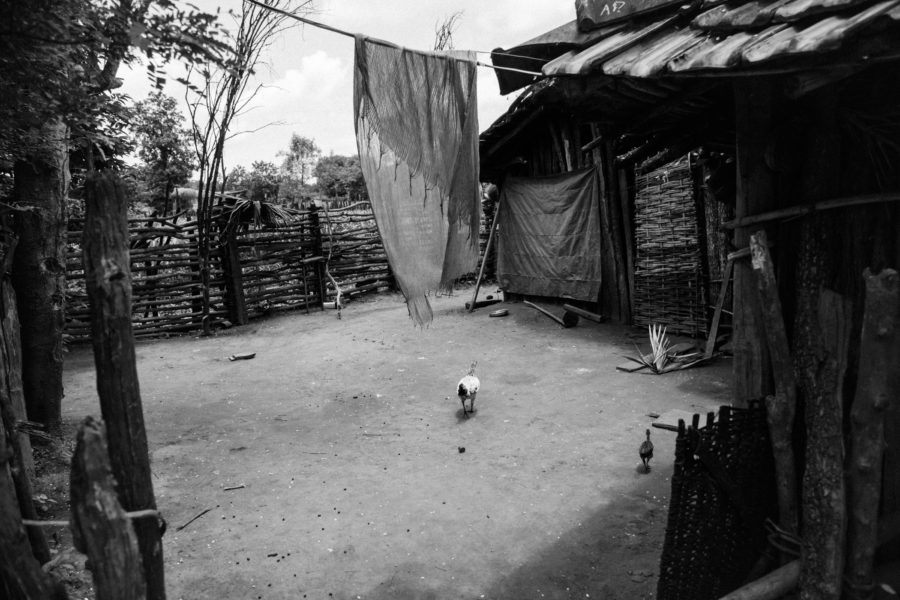

A recently felled tree in the forests at Balimera. The Murias clear large patches of the forest for farming and to build settlements, inviting the wrath of forest officials.

In 2004, Madakam Lachmi’s 19-year-old brother and three others were shot dead by helicopter-borne Salwa Judum assailants while they were fishing at the village pond. Terrified, Lachmi and her mother moved with 50 other families from the village into the forest, where they lived for three years before migrating to Tellarayigudem.

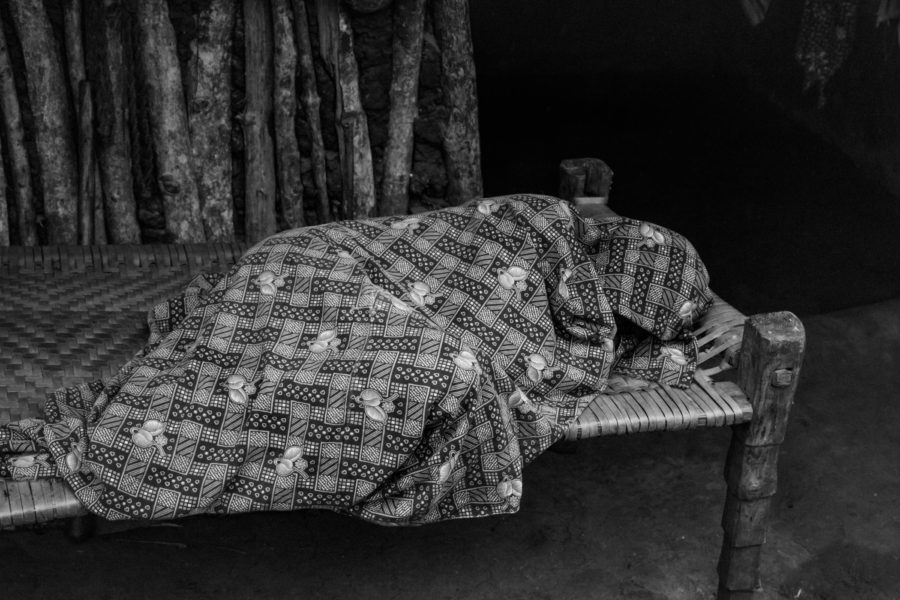

A sick man rests during the day at Tellarayigudem.

Muchakki Ungi (left) threshes paddy in her house in Tellarayigudem.

All men in Lankapalli between 16 and 40 years of age must report at the police outpost in Edugurrallapalli every week without fail, or risk being branded Maoists. Villagers dread these visits to the outpost, where they are beaten up and made to work without pay.

A woman carries paddy seedlings to a field in Thatigonde. The Murias practise an inefficient form of agriculture and the yield barely meets their needs.

On January 23, 2012, in a ‘routine’ search operation, Central Reserve Police Force personnel surrounded Nimmalagudem on the Chhattisgarh side of the border and arrested Madvi Parvathi (22), who was two months pregnant, along with another girl, Kovasi Somidi (16). They were beaten with rifle butts and then dragged through the jungle for three days. Parvathi was illegally detained in jail for three months and suffered a miscarriage.

At Tellarayigudem, men return from cutting wood in the forest for a contractor.

Soyam Chilakamma stands in front of her hut in Aalubavi, which forest officials destroyed. They took away money and valuables, she says. The villagers have since moved to an adjacent plot of land in the next village.

A family fishes in a small stream around lunchtime in the forest around Balimera.

A Muria man, fetching water, walks past a church in Ramachandrapuram, an early Muria settlement in the region.

Soyam Lachimi in a temporary structure in Kondapuram built after forest officials destroyed their house in Aalubavi.

A young Muria at Thatigonde.